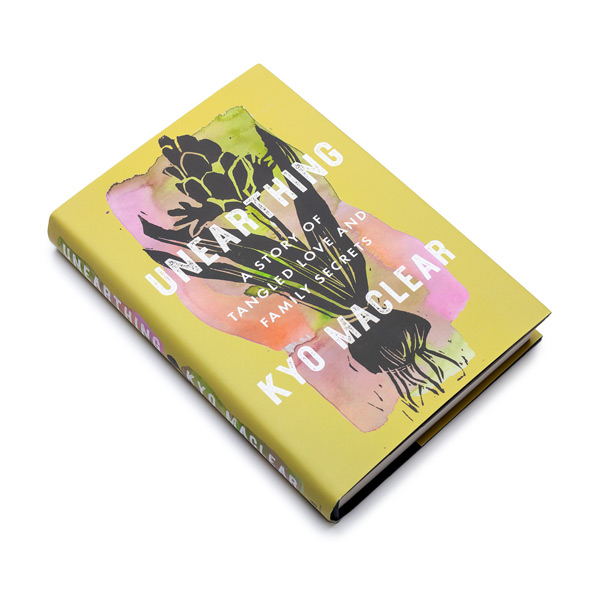

PROLOGUE

Ma was a gardener. Where she saw gradients of celadon, emerald, sage, olive, I saw only a thin green blur. When given a plant by someone who thought I looked capable, I would start out full of hope. I admired the buds for opening with confidence and the buoyant way the leaves unrolled. But before too long, the sprightly leaves would wilt or crisp. The Madagascar jasmine, enfeebled by too little sun or not enough water, would sigh toward the ground. The peace lily, overflooded with daily attention, would sag and expire. All the sad plants . . . I could not, in spite of my mother’s effortless example, and my effortful efforts, keep them alive.

Then things took an unexpected turn and what I had dismissed as not for me but for my mother suddenly moved to the fore. In early spring, 2019, it was determined through DNA testing that I was unrelated to the man I had always thought was my father. Well into the journey of my life, the imagined map of my family, with its secure placement of names and borders, was suddenly very wrong. All at once, my silver-haired mother became unknown to me. She had a big story to tell, a story of a secret buried for half a century. A story that she struggled to express—or had no wish to express—in her adoptive language, English.

I wanted my mother’s story. I wanted a tale that could put my world back together. But each time I pressed, my mother shook her head.

My mother had never really liked stories. She looked at them with suspicion. All my life she questioned both the ones I read and the ones I wrote. All my life, she asked: What are you doing? And nine times out of ten, I replied: I am writing or I am reading. Both answers brought forth the look. The look rightly asked, What purpose is there to your efforts? The look accurately said, No one can eat a story, no one can dine on a book. On the rare occasion someone commended my writing in her company, she bore a weary smile. A smile that pitied the speaker for not realizing there were better, more reputable products out there; better, less soft ways to spend a life. But the look also said: Don’t squander it. Write something worthy and practical . . . write a plant book.

In 2019, what did and did not work between us was now irrelevant. All the ways we had been at odds in life no longer mattered. I needed to understand my mother better, and the only way to do so was in the language she knew best. Given the state of my forgotten first language, Japanese, I chose her second fluently-spoken language, the one she never pushed on me: the wild and green one.

This is a plant book made of soil, seed, leaf and mulch. In 2019, I turned to the small yard outside our house and the plants my mother had woven into my life, to bridge a gap between us. The yard was scruffy and overgrown. It belonged to the city, to the bank and, most truly, for thousands of years, and still, to the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg. With my sleeves rolled and my fingers mingling with the rose-gray earthworms, I set to work.