A few weeks ago, I spent several cold February afternoons at a book morgue, otherwise known as The Monkey’s Paw, a second-hand bookshop in Toronto. I go there regularly but on those particular afternoons, it was a refuge of sorts. I had been feeling slightly down about writing and wanted to linger in a place of pure bibliophilia. Like many novelists, I experience an existential crisis every time I finish a book. Why bother? Why engage in such an intangible and self-involved vocation when I could be doing something more tangibly and socially useful (e.g., stopping a pipeline, regrouting the bathroom)? Why write long-form narrative in a world that prefers to live swiftly and episodically (et cetera)?

In the past, this soul searching has lodged itself in the personal-neurotic realm. But lately it has ballooned into a broader crisis about how much less novels matter now to the mainstream than when I started writing.

I don’t want to sound self-pitying or ungrateful (after all, I’ve been fortunate) but the work of writing novels—literary fiction, no less—just seems an increasingly weird and arcane thing to be doing with my time. It’s fairly obvious when I look around that fewer and fewer people I know and love are reading books. (And here I’m not referring to people who opt to read books onscreen over ones in print—I’m talking about reading books period.) They don’t see the point. They’d rather be watching Downton Abbey or clicking through obscure indie news sites. They would prefer to be resting in supta baddha konasana or hanging out with circus friends in the park or blogging at their local coffee joint. You get the idea. They are drawn to culture, just not the culture of reading books. And to my dismay, this lack of books does not seem to have left a yawning void in their lives.

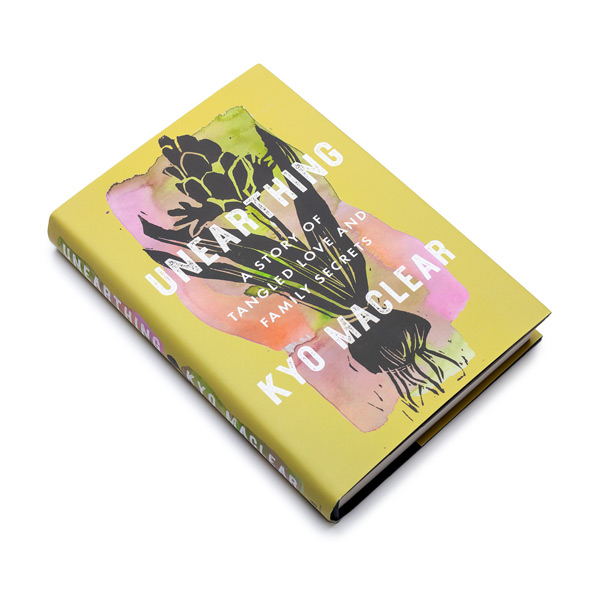

So, I spent time at The Monkey’s Paw, feeling disgruntled about the ailing state of the literary novel; grieving somewhat for myself and my forthcoming effort (what a way for a new book to begin—intubated, on precious life support); and grieving for my children (what are the “soul effects” of choosing Angry Birds over Lewis Carroll?)

What compounded my despair was the feeling that it needed to be borne stoically, in silence. Of course I was silent. Any novelist with her head screwed on properly knows better than to announce publicly that the novel is doomed. As Jonathan Franzen cautions in his book How to Be Alone: “However sick with foreboding you feel inside, it’s best to radiate confidence and to hope that it’s infectious. . . . In publishing circles, confessions of doubt are commonly referred to as ‘whining’—the idea being that cultural complaint is pathetic and self-serving in writers who don’t sell, ungracious in writers who do.” In other words, no unseemly griping, no joyless defences of publishing, no intellectual shaming of non-readers, et cetera. No matter what misgivings may flicker beneath the surface, the smart writer knows to present herself as a polished and sanguine human.

This posture of dissimulation started me thinking about the tradition of non-disclosure in Japanese hospitals. Two of my uncles died without knowing they were terminally ill. One thought he had appendicitis. The other thought he had lower back pain. I began to wonder: What if the book were a patient in a Japanese hospital? What if it were actually doing more poorly than anyone would admit? I know what you’re thinking. People have been saying for what seems like forever that the book is dead. But what if it is really bad this time? What if the book is truly and irrevocably breathing its last?

It was while chatting with Stephen Fowler in his beautiful shop that I had an epiphany. At any given time, his bookshop is packed with 6,000-plus dead titles on everything ranging from terrestrial slugs to false hair. Rows of books are in peaceful repose on tables: gorgeous idiosyncratic corpses that would excite any literary necrophile.

I don’t think a single title in Fowler’s collection would be considered commercially viable if published today. (Some are barely readable. One can only imagine the prose challenges of a book called Carp: How to Catch Them.) Yet, oddly, it’s one of the least depressing bookshops I know. Even the bad books are not bad in the usual vapid, trite, cynically formulaic way. They are uniquely, bizarrely, captivatingly bad (e.g., Vans and the Truckin’ Life, The World of Clowns, The Problem of Being An Icelander: Past, Present and Future). And a sense of strange beauty and calm pervades the shop. Fowler who describes himself as “the youngest person to come out of the old book trade,” and who was recently invited to join the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, has created a genuine Mecca for book-lovers.

He has done this not by championing literature’s survival. Not at all. Fowler has accepted the book’s demise. In fact, having passed through the customary stages of grief, he may be the only person I know who can openly say, and with a smile, that the book is dead.

I was there one afternoon when he had just returned from a buying trip in the Niagara area. Sitting there, I watched as he went through his newly acquired stack, thoughtfully pencilling in a price and sometimes a word or two (quaint, uncommon, macabre, obsessive!).

A man browsed through the “Ego Annihilation” section (books on sex, drugs and death). A woman flipped through an expired copy of Creative Wood Craft (a store bestseller). These were not calls of condolence. These customers were not looking for scented candles, bath salts or other non-literary tchotchkes. They had come to engage in the primordial, timeworn practice of pulling books at random from shelves and opening them to see what surprises lay inside. Inspired by what I saw, I also browsed. I browsed through the slowly aged Penguin paperbacks and the bird book that cracked when I opened it. I looked through the poetry and film sections. I bought a book by Igor Stravinsky and a copy of Amerika by Kafka exquisitely illustrated by Edward Gorey.

By the time I left, I felt buoyant. It dawned on me that this is what happens when you are done with mourning. This is what is left when you pass through denial, rage, wallowing, when you lose the desperate edge of your grief: you free yourself up for other emotions, including curiosity and love.

I’ve heard people say that as the publishing industry rapidly realigns to meet the digital age, antiquarian books and fine press books will thrive. I don’t know if The Monkey’s Paw is the bookstore of the future but, for me, it is a nice place to spend time; a place to befriend the dead.

As writers, perhaps the best we can hope for is that our books leave beautiful corpses, that they will be loved for what they are, visited occasionally, tenderly maintained.

I realize that this may not be your definition of a successful life, but it’s enough for me.

Originally published by The Millions (March 12, 2012)